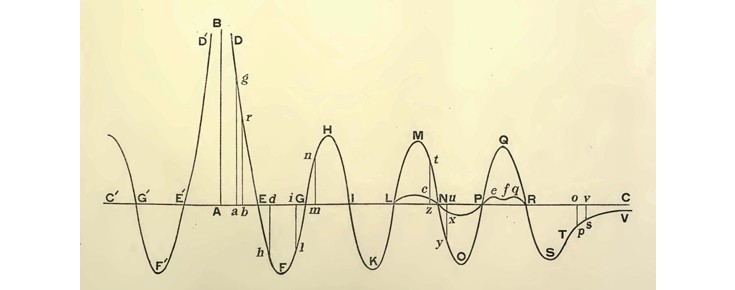

The present paper examines Boscovich’s conception of force as it emerges from his early writings in mechanics and natural philosophy as well as in his Theory of Natural Philosophy, Reduced to a Single Law of the Forces existing in Nature (1758, 1763). “Although the title to this work to a very large extent correctly describes the contents, yet the argument leans less towards the explanation of a theory than it does towards the logical exposition of the results that must follow from the acceptance of certain fundamental assumptions.” These are the opening remarks of James M. Child’s introduction to the English edition (1922) of Boscovich’s Theory. In the following pages, Child would expose such premises, underlining a surprising point that seems to be in tension, if not in blatant contradiction, with the title of the work by the Dalmatian savant. Boscovich’s “mutual vires”, Child explains, “are really accelerations, i.e. tendencies for mutual approach or recession of [pairs of] points, depending on the distance”. So there would be no forces really existing in nature, after all.

In the 20th century an increasing number of scholars would become interested in Boscovich’s work. Partly reacting to Child’s introduction, many of them pointed out that in Boscovich’s theory the features of matter — first of all, impenetrability — are explained in terms of an interplay of forces, whatever the term “force” may denote, and they began to suspect that Boscovich’s cautious “Newtonian-style” warnings about the reality of forces simply obscured his most profound insights.

In the present paper I contend, however, that there are fundamental differences between Boscovich’s theory and the “dynamical (force-based) theories of matter” in vogue at Boscovich’s time. Moreover, text-based evidence from Boscovich’s Theoria, as well as from other works in natural philosophy and mechanics, suggests that Boscovich never made hidden conjectures on forces; it hints instead at some novel insights about the role of mathematics in his work. In particular, I suggest that Boscovich envisioned in mathematics the possibility of overcoming potential discrepancies between divergent interpretations of physical phenomena. There might have been many “theories” of them, but there was only one mathematical structure that united them.